40 Years of Teaching and Learning with Nelson File ’78

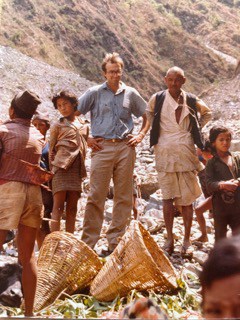

Nelson File ’78 has been a teacher abroad for nearly the entire time since he graduated from Abington Friends School. His journey and call to service has taken him all around the world—volunteering with the Peace Corps in a village in eastern Nepal, and then teaching in Kinshasa, Zaire [now the Democratic Republic of the Congo]; New Delhi, India; Muscat, Oman; and most recently, Hobart Australia, where he serves as the Headmaster of The Friends School, one of the largest Friends schools in the world. As he prepares to retire at the end of the 2023 school year, Nelson agreed to speak with Oak Leaves about his career, what he’s learned from teaching all over the world, and the value of a Friends education.

Take me back to when you were studying at Abington Friends School around 45 years ago. Did you know that you wanted to be a teacher after you graduated? As in, I’m gonna be the Head of School of Hobart one day, so I need to get on my path right now?

Oh no. *laughs* I think as my career unfolded, it was never necessarily planned.

Abington Friends turned out to be a great educational opportunity. There’s a long list of teachers from that period I still remember quite fondly. Mary Helen Bickley and Carl Bremer and Tom Moore. I saw recently in Oak Leaves that Mademoiselle Yannick Tanguy, who taught us French, had passed away.

Ed Thode was Middle School principal at the time, Alice Conkey was the high school principal, and Adelbert Mason was headmaster. Although you didn’t have much interaction with him, there was deep respect for him and his work. He was also instrumental in getting me my first teaching job at Friends’ Central. Terrific staff, terrific colleagues. I enjoyed coaching, I enjoyed working with kids, I enjoyed working with teenagers. But most of all, I loved the I Got It moment, when kids light up with understanding. And that’s really what’s driven my career.

Where has your career taken you?

Well, I met my wife when we were both serving in the Peace Corps. You don’t hear about it as often today, but the Peace Corps really offers this incredible grassroots interaction with people around the world. It’s soft diplomacy for America—which is a good thing—and you witness firsthand how a couple billion people in the world live at a real subsistence level, working as hard as they can to feed their family with modest means to do so on tiny patches of land. It gives you a unique perspective.

After that, my wife and I taught in American International Schools all over the world, in Kinshasa and New Delhi and Muscat. I had never been to the Middle East before moving to Oman: The only country that I had ever visited was Canada because of a year 11 French trip from AFS. So I had never been out of the United States or Canada before answering the call of service to serve in Nepal. But instead of just visiting for a week or two, we felt the best way to better understand the world around us was by living in places for extended periods of time.

It has been fascinating, and very instructive, to compare the local religions in these regions back to my own upbringing as a Quaker, and being born and raised in a long-term Quaker family who always attended Meeting for Worship. Quakerism believes that everybody finds their own path to the truth, expressed through some sort of religious practice that might look different from your own. Although, I would have to say I was more rebellious during my teenage years. When I was like, you know, “I’m already going to Meeting for Worship with Abington. Why do I need to go again on Sunday?”

You book-ended your career with two Quaker institutions—Friends’ Central and The Friends School—but in between you taught at American International Schools all over the world. What’s the difference in your mind between a Friends education and other systems?

When envisioning the role of Friends education, William Penn wanted to use education to populate his colony with virtuous and just people. In his vision, they wouldn’t need a court system or a police force to enforce the law if everyone was virtuous. He also wanted people to be educated in useful things, so that the community was full of contributing members to society. And I feel that’s true at all Quaker schools: They aren’t just educating you to get the highest grades to get into the best university, they’re educating you to be the best possible person you can be.

Abington Friends is one of those original schools that heeded the call of William Penn. He asked each Meeting to educate all children wherever the school was located, regardless of religion. So many other early schools were based upon if you were Anglican, if you were Catholic, but the history of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia was that of complete religious freedom, because Penn and the early Quakers believed that everyone would find their own path.

It’s clearly articulated in the mission statement at The Friends School—which I think is excellently written—we want students who are going to think clearly and act with integrity, have care and concern for others and the environment, be great in service and hold a global perspective. Who doesn’t want to live in a society if everyone’s acting that way?

No, that sounds perfect.

I think the unique strength of Quaker schools is that they strive to see that of God within everyone, and treat students as equal. That’s a key commonality of teaching at any Quaker school—creating that environment of respect and responsibility. Respect doesn’t come from titles and rituals, it comes from the deep understanding of how we see each other.

My wife and I hoped that at some point in our lives, some of our children could attend a Quaker school and receive the same quality and caliber of education that I received at AFS. So our two youngest finished their high school years here at The Friends School in Hobart. Our son came for years 11 and 12, and our youngest daughter came for years 10, 11 and 12.

What are the big challenges that the next generation of educators will need to face?

Look, I think schools are always being asked to do more and more. Student well-being and student mental health, and staff well-being and staff mental health—they are all such key issues and concerns. Unless kids are feeling good and staff are feeling good and positive, you know, they’re not going to be in an environment where they can learn at their best. At the same time we can’t have that desire to make the perfect environment consume us.

But I think Quakerism is so well suited to solving these problems. Every week in Meeting for Worship, there’s 45 minutes where you’re switched off. You’re not scrolling social media. You’re not being distracted or being asked to chase after this or that. Students benefit certainly, but I also think a lot of adults could do with switching off for a 45 minute period every week.

We seek to help our students develop as people who will think clearly, act with integrity, make decisions for themselves, be sensitive to the needs of others and the environment, be strong in service and hold a global perspective.

The Friends’ School’s Purpose and Concern Statement

Quakers have been doing that for 350 years, right? This fostering of mindfulness has always been a part of Quaker education.

What’s your advice to students who are just now graduating and might be overwhelmed with all the different directions they are being pulled in?

There’s a lot to be confused about. Sometimes there seems to be an ocean of options, but nowhere to really start. You are told repeatedly to follow your passion, but you might not know what your passion is. That’s not bad: Young people may not have had the opportunity to experience what they’re going to be passionate about 10 or 20 years from now. But you can always turn towards their interests—what provokes you, what makes you wonder?

When I was a year 12 at AFS, there’s no way in the world that you could tell me I’d spend my entire professional career living abroad, and that I’d end up as the Head of School of a Quaker school in Hobart, Tasmania—which I would not be able to find on a map in 1978 when I graduated! I did not know that would be my passion. But I did know that I was at least interested in it.

If you’re graduating from AFS, that alone gives you plenty of tools to move forth into the world with confidence. Remember: Think clearly and act with integrity! Have concern with both yourself and others! Everything else will fall into place.

I appreciate your insight, and thank you so much for talking to me today. This has been a truly great conversation.

That’s kind of you to say. All the best to you, the school community, and the Class of 2023!