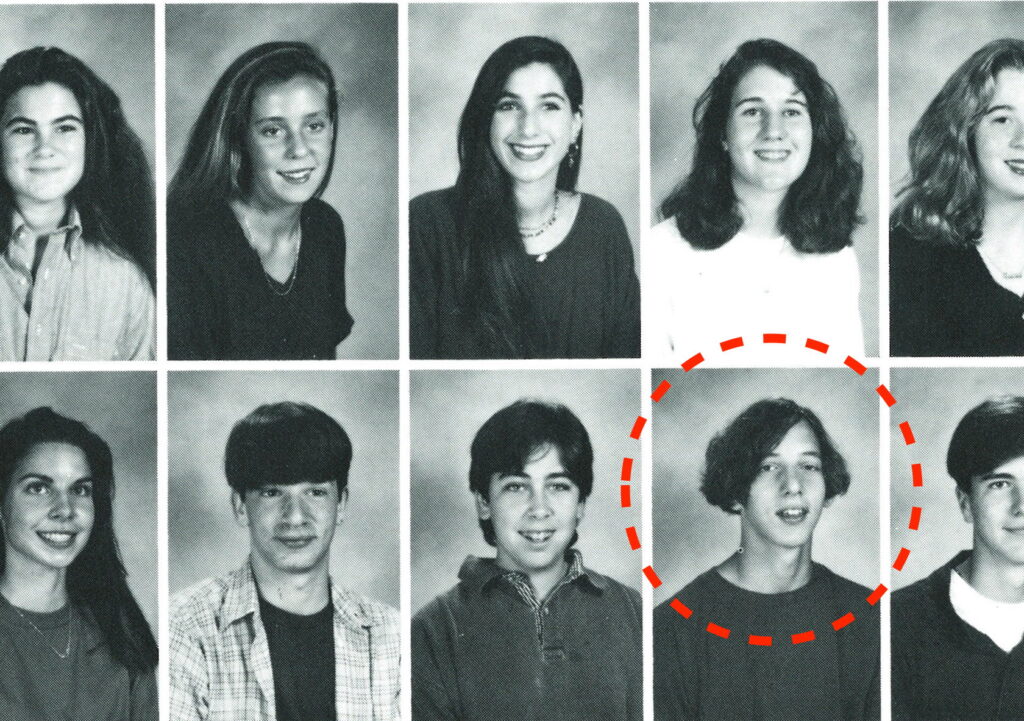

What Do We Do With Our 80,000 Hours? Listening to Your Leading with Jon Makler ’95

Jon Makler ’95 quit his job at the Oregon Department of Transportation for the third time in the summer of 2022. As a project manager and urban planner he had worked trying to shape policy toward making society more equitable. Now, as a manager for the Northeast Emergency Food Program, Jon’s impact has become more direct. He coordinates a dedicated corps of volunteers to support and oversee the collection and distribution of grocery products to families with urgent food needs in the Portland metro area.

Between an office job and the hands-on daily challenges of running a food bank, there is a world of difference—so what was it that caused Jon to make the decision to change paths?

“I have spent 40,000 hours of my career so far, and I probably have another 40,000 to go,” Jon explains to me. “That’s 20 years at 2,000 hours a year. I enjoyed my 20 years as a transportation planner, but transportation planning wasn’t the essence of my career. The essence of my career—the journey that I began at Abington Friends—is really one of being a humanitarian working toward peace and justice.”

Jon traces a direct path between his work today and his time at AFS. At the time, there was no difference between trash and recycling; everything went in the same bin. As a 9th grader in 1992, he wanted to create a recycling program. So he went to Debbie Stauffer, then Assistant Head of School, and explained his plan.

“I told her, ‘I want the school to have a recycling program.’ And I proposed to do it—I would go buy some trash bins, label them, and form a club. My family’s station wagon would be the trash truck, and we’d haul everything off to the dump ourselves. And she said, go for it!”

Debbie, who had been at Abington Friends School since 1975, had seen her share of student changemakers in the years before and until her retirement in 2017—but Jon stood out to her. “Jon was an amazing kid,” she says. “I certainly didn’t want to stifle kids’ creativity or initiatives. Recycling, well, it was a good idea.”

It is easy to imagine a bunch of Upper School students hauling tubs of cans and bottles from all over the school, rinsing them out and stomping on them so that they could fit in the back of a parent’s car. It might be fun with your friends for a day or two, but to do it week after week, you need something more than the fun and novelty of a new project driving you. To keep the energy going, you need to feel called to answer the moment in a more profound way.

“That sort of began my journey of being able to act on a leading, as we would say in the Friends Community,” Jon reflects. “Through being supported by the school community, by my friends, by my mom and her car, I learned to not only recognize a problem, but then do something about it.”

In Quaker practice, a leading is a way in which Friends are called or moved to do something by the Spirit. Students at AFS are familiar with the concept through their participation in Meeting for Worship: Community members gather together to sit in silence, waiting for times when we are moved to share something with the group. A lifelong Quaker, Jon’s leading to make a change in his career began to re-emerge when he and his family decided to take a sabbatical and do a gap year for the 2019–2020 academic year, spending time traveling across the United States and the world. They made it to Southeast Asia in late February of 2020, and… you can see where this is going.

“The world started to seriously shrink,” Jon explained. “We came home, and I returned to my transportation career for another year. But I sort of self-radicalized on the trip. When we were in lockdown in Malaysia, we were in an apartment in the city of Johor across the strait from Singapore. There were about a thousand units in one building. A thousand units! That’s thousands of people in three towers, 40 stories each, 10 apartments on each story, all on where Americans would fit one Home Depot. The urban planner sees that and goes: My God. In Portland, we’re fighting for 5-on-1, where you build one floor of concrete for retail and then five floors of residential on top. That’s considered density here.”

The distance between what he wanted to be able to pursue as an urban planner and the more incremental changes he was actually making began to feel irreconcilable. When Jon arrived home during the pandemic, the leading became even stronger. Jon believed in working within the system to make change—like starting the recycling program at AFS—but the change he was looking at making was hard to come by. (“I had one mentor in my equity work who said, Jon, if you’re a changemaker, then every day is going to suck. Because if change was easy, we wouldn’t need changemakers.”) With 40,000 work hours in his life to go, his leading was telling him that there might be another way.

“There was a rapid change in the visible poverty exposed by the early pandemic,” Jon explains. “They didn’t have housing. They didn’t have food. Almost overnight. And I just didn’t feel like I could justify making transportation a priority. I was going to make a change one way or another.”

Jon suspects that a lot of people in the AFS community have this thought process dwelling inside of them because of the way they were educated. “Self-reflection is so vital to maintaining a clear sight into why you are doing anything—it’s the key to unlocking questions that otherwise seem really stressful.” Above and beyond the education that he received at AFS, Jon values the moral dimension of Friends teachings, the tenets of Quakerism that the AFS student is immersed in that lie outside of the standard story about professions and careers as ways of life, and more as vehicles for values. You might feel like you are called to do one thing, that you have skills that you can put to use in one particular area, but you are always asked to reflect on what those skills are used in the service of.

There is a link, Jon recognizes, between the work that he is doing now and the work that he started back at Abington Friends School. Being on the ground doing physical labor—whether that’s moving a school’s-worth of recycling or processing 25,000 lbs of food per week—is not romantic; it was simply following his leading. And Jon can trace this leading back to his time sitting in the Meetinghouse at Abington, and see that as the formative experience of thinking of himself as a member of a group.

“When I came to her with the recycling idea, Debbie could have responded very differently to this disruptive force,” Jon said. “Instead, she directed me and funneled me toward my goal. She really fostered my passion for service in that way—giving me a lot of grace, a lot of latitude.”

Debbie knew she couldn’t say yes to every single idea a student came up with—she didn’t even say yes to every idea Jon came up with!—but seeing Jon’s passion for the work showed her that he was someone she could trust. “I had to look out for the whole school and make sure any student’s projects were good ideas that fit in at AFS,” she explains. “I trusted Jon to do what was right then, and I’m proud of all that he’s doing now.”

Thirty years later, Jon still carries that trust within him—that little seed of service that has since blossomed into a leading to not only do good, but increase the good he can do in every way.

“My life experience has reinforced the need to define community broadly, and continue to practice to apply to serve my community and not just myself,” says Jon. “So my calculation is very simple: With 40,000 hours to go, how do I maximize what I can give to society?”