Envisioning Our Future

Hands in the Dirt, Minds at Work

Inspire Authentic, Transformative Learning through Experiential Learning

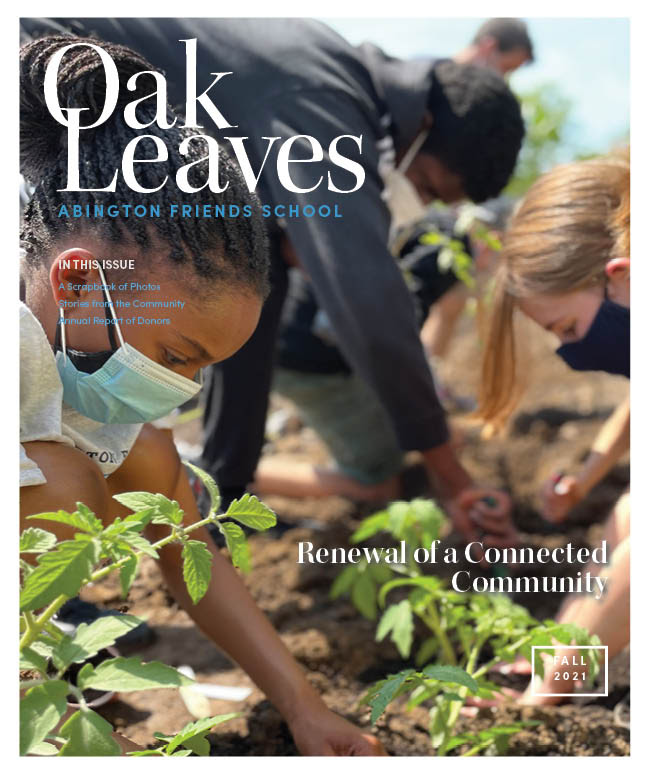

Once upon a time, outside of the AFS cafeteria there were some raised beds that had been on the property for some time. Then, one day a few years ago a group of teachers commented how great it would be to be able to capitalize on the beds and use them for clubs and science class. Not long after, a mix of teachers, students and volunteers pitched in during the Spring Break of 2021 to construct what has come to be known as the Meadow Garden.

“Given that we had been apart for some time due to COVID-19, it seemed like the time and place were ripe for us to be able to do this,” says Mike McGlinn, who has been a middle school teacher at AFS for five years. After getting everything set up and in the ground, he got a group of students involved in helping maintain it.

“They seemed to really gravitate towards the whole idea of working under the sun and seeing the fruits of their labor,” says McGlinn, who loves the fact that this kind of work gets students away from staring at screens all day long. “That’s beneficial to them, health-wise by being outside, but also [it’s great for] social-emotional learning.”

Nikki Kent, a middle school health teacher at AFS for nearly 20 years, agrees that outdoor learning is hugely beneficial.

“The school’s policy during the height of the pandemic was to be outside as much as possible,” says Kent, who also taught science this school year. “This was a great way to get kids out there doing something meaningful.”

Getting outside and digging in the dirt inspires authentic, transformative learning in the science classroom. A lot of kids don’t know what goes into their food or what kind of practices are involved that might not be healthy for them or for the planet. By working in the Meadow Garden, however, students get their hands in the dirt and are there for every piece of the growing cycle. They learn the science behind it, food justice and sovereignty throughout the process.

“What I absolutely love is the kids are willing to try vegetables, and they’re proud of their vegetables,” says McGlinn. “They don’t want to waste anything. When Nikki and I go around with the peppers in the fall that have come out of the garden, there’s a real sense of ownership and attachment, and the kids have a sense of inner joy about it.”

One day the class decided to cook kale in oil with garlic and salt.

“The kids absolutely loved it,” says McGlinn. “I’ve never seen a group of fifth-graders munch down on really healthy vegetables like that.”

The following week when a bunch of kale had been harvested, a fifth-grader asked McGlinn what he should do with it. McGlinn told him to take it home and cook it for his mom because he now had the skills to do that.

“It was really cool to see that a-ha moment for him,” says McGlinn. “We’re giving these kids tools of self-reliance.”

In today’s world, so many kids want quick and easy food. That often translates to processed foods. Kent likes to show how vegetables like tomatoes, mini peppers, and edamame are easy to pick.

“I think the Cooking Club is one of the best things we’ve done because we took the things that we grew and had the kids cook them fresh from the garden,” says Kent.

Last year, teachers gave students several plants to take home and grow.

“That, to me, is huge when a kid learns a skill in school and then takes it home and uses it with themselves or a parent,” says Kent.

The Gardening Club is now an actual class that’s become increasingly popular. Kent believes its popularity stems from the fact that students are going out and learning something organically and not even realizing it.

“It’s amazing. We start off every year with one or two kids, and it grows and grows,” says Kent. No pun intended. “Kids like to do things. They like to be busy. They don’t want to be reading 100% of their day. They want to be doing things with their hands.”

While it may seem like kids would naturally gravitate to, say, a Minecraft Club, the Garden Club appeals to them because they get to see tangible evidence of hard work. AFS teachers have found that creating an experience of learning through doing is the best way to teach because it puts ownership on the students to take control of their own learning.

“There’s more buy-in when there is real-world application,” says McGlinn.

Middle-schoolers, in particular, benefit from this way of teaching.

“I find fifth-graders to be very enthusiastic and still embody an innate curiosity, whereas eighth-graders are ready for something that’s more intellectually stimulating,” says McGlinn. “There are ways to do that all over the garden, and that’s been pretty awesome to be able to work with both age groups there.”

He says that he enjoys teaching middle school because students are capable of accomplishing so much in the world even though they often don’t get credit for it.

“For the general scope of what we cover, especially in eighth grade, these are kids that are being told no all the time. And when you give them some responsibility, a lot of times they rise to the challenge,” says McGlinn. “They’re also not bogged down by a more rigid, stringent curriculum like the upper schoolers. So I think there’s a lot more curricular freedom to be able to expand.”

According to Kent, teaching environmental science and sustainability is everything.

“We’re so reliant on resources, and we all know what’s happening in the environment, so these are just key things,” she says. “In 30 years, these will be the leaders. And the fact that they’re learning the impact now, hopefully we’ll help them become industry leaders, looking after the environment, looking after sustainability. We’ve moved away from that as a world, and it’s time to go back.”

Adds McGlinn, “The Earth sustains us. We don’t sustain the Earth.”

The students who were instrumental in the creation and maintenance of the Meadow Garden are:

- Esa McCants

- Oliver Peterson

- Niels Rush

- Nelson Cordon

- Miranda Shandell

- Kieran O’Donnell

- Yael Smith-Posner

- Jeffery Scott

- Alyson Cromar

- Mayalondyn Gray

- Catrina Reinhold

- Margaret Richards

AFS Hires Director of Experiential Learning

Over the past ten years, experiential learning programs have expanded dramatically at AFS as a key part of our strategic vision. Central to Quaker faith and practice, we believe that experience itself, well-designed and reflected upon, is essential to powerful, transformative learning. Through the Center for Experiential Learning, we have created innovative programs for cohort mentorship in fields such as medicine, law, business and farming; a global travel program; ExTerm immersive, interdisciplinary classes in the Upper School; a powerful Senior Capstone program of pursuit of deepest interests; and a program called AFS Explore that guides individual students to a wide range of external programs in science research, business, medicine, climate activism and leadership.

The spirit of experiential learning is growing in all divisions of the school, and we are excited about how this type of programming for students and teachers will continue to transform what school in the fourth century of Friends education can look like. To that end, AFS has hired Adena Dershowitz as Director for the Center for Experiential Learning—a position previously held by Rosanne Mistretta for several years. Dershowitz, currently Head of Middle School at Lycée Français de New York in New York, New York, officially joins the AFS community this summer.

“Education is not preparation for real life, but rather the years between ages three to 18 are a vital part of real life. As we do for adults, we hope that children live with joy, with purpose, and with impact. Experiential learning assures that students get chances to discover, to connect, and to make a difference in the world,” says Dershowitz. “Experiential learning takes many forms: digging for worms, collaborating with an artist, or immersion in a new culture or workplace. These experiences shape our learning and the way we make meaning of the world. They frame children’s ability to be better students, and to be healthier and more fulfilled human beings.”

Dershowitz will be collaborating with AFS faculty, students and school leadership school-wide in continuing to explore and develop opportunities and classroom curriculum for engaging students with the wider world. She will also be responsible for fostering and growing relevant community partnerships with businesses, organizations, alumni and parents to connect AFS students to internships, service learning and other experiential learning opportunities.

Dershowitz will continue to develop and oversee the Upper School’s experiential learning cohort ExTerm, Senior Capstone and the school’s Global Travel program. In addition, this new role represents the Center for Experiential Learning internally as a member of the Administrative Council and to the public at Back to School Nights, Admission Open Houses and in the external community at large as a spokesperson for the Center through partnerships. She also will lead the Faculty Council on Experiential Learning which will facilitate collaboration, consultancy and generative thinking in regards to curriculum.

“Adena emerged as a deeply insightful educator and school leader, well grounded in Mind-Brain Education research and social emotional learning with vision and passion for student centered, active learning,” says Rich Nourie, Head of School. “She’s passionate about creating authentic, transformative learning experiences for students with her colleagues.”

Dershowitz, a passionate educator and school administrator, devoted wife, and mother of five-year-old twins, has experience teaching children of many age groups as well as developing professional learning for faculty. She has success in developing curricular programs, assisting in the design of learning spaces, and creating and implementing new initiatives. She says she’s enthusiastic about joining the AFS community for a number of reasons.

“I was struck by how Quaker values and commitment to the whole child are truly lived day-to-day,” says Dershowitz, who visited classrooms in the lower, middle, and upper school when she was on campus. She was impressed by how students were actively engaged in their learning about important and resonant topics. “My conversations with adults in the school led me to realize that AFS is at the forefront of doing what’s best for children and adolescents,” says Dershowitz. “I’m looking forward to collaborating with the incredible faculty and staff to provide meaningful learning experiences for all students.”

Constructing Lives of Purpose, Meaning and Contribution

Fully Envision and Live the Promise of Equitable, Inclusive Community

Students at AFS have embraced the chance to be a force for positive social change as they work closely with their faculty members who are forward-thinking about their teaching practices. One example of this work is in the Upper School’s History department, led by Chair Margaret Guerra. Guerra, who has been teaching history at AFS since 1997, notes that the pandemic marked a turning point, as it allowed teachers to restructure classes in partnership with students.

“My students shared how they were feeling, what motivated them, and what parts of our work resonated,” says Guerra. In short, everyone craved collaboration, which makes sense as collaboration is at the root of all meaningful learning.

In May 2020, as COVID-19 was ramping up, the movement for racial justice also took center stage in the public eye.

“Our students, whether racial justice work was always part of their lived reality or not, felt the urgency and possibility of change,” says Guerra. Throughout the 2020-2021 school year, many of AFS’ Black students shared their experiences in classes and in the world. Their strongest messages were, “Listen to us. Don’t rush to ‘fix’ [anything.] We need to see ourselves in the adults in our community and in our curriculum.”

Director of Equity, Justice and Engagement Mikael Yisreal weighed in on the importance of being intentional in building a diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) strategy saying, “We, as a community, must be intentional about building DEI into our institutional priorities, policies, and programs. It is imperative for this work to be foundational and core, not viewed as peripheral or value added. He adds, “A true commitment to DEI stems from continuously defining and refining, focusing and refocusing our individual and institutional lens in an equitable and inclusive way; centering and celebrating our rich diversity, shared humanity, and divine dignity.”

Yisrael and the students also felt that representation in the curriculum must include Black joy, Black power and the diversity of the African diaspora. During the summer of 2021, AFS’ history department held a two-day retreat to assess what had been learned the previous year and to plan for the future. Front-and-center were questions of representation in the curriculum.

“One of the many tensions in our work is to teach honestly and openly about systems of oppression, yet allow our students to understand that people who experience oppression also experience joy and create rich lives,” says Guerra. Another component of the work is to collect primary sources by many different people, including people who had the least access to literacy and preservation of their past.

Senior Sanaa Nicholson has poured a lot of energy into DEI work during her time at AFS. As she became more immersed in the work, her knowledge and expanded thinking naturally came with her into the classroom. This shift in thinking occurred most notably in her history classes, where during each unit she repeatedly asked herself, “What were black people doing and thinking during this time?”

“The way I’d been taught history in the past was that African-Americans only existed during slavery, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Obama presidency,” says Nicholson. “Because of this lack of representation, I was fairly unengaged in what I was learning.”

Nevertheless, she never lost her underlying love for history, learning, and historical analysis. So when she was presented with the opportunity to write an independent research paper, she was extremely excited.

“I would finally be able to learn about people who looked like me, focusing on a topic of my choosing,” she says.

The following year, Nicholson became clerk for the Black Student Union. She met with Guerra and was given the opportunity to conduct an independent study during her senior year, along with her classmate Gabby Warner. Nicholson studied different approaches to black liberation as well as black joy, while Warner focused on the Black Student Movement and student activist groups of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

“Not only am I getting to look into topics about African-American history, but I am also creating lessons to teach to ninth-graders,” says Nicholson, who chose topics that focused on holding African-American history in a positive light. For example, she researched black music as a vessel for joy. She also focused on topics that had to do with the intersections of identity; this included black queer history and black art.

“I wanted to break down the narrative that there is only one way to be black. This is why the student voice is so important,” says Nicholson. “If I were sitting in history class in my freshman and sophomore years, learning about black queer womanist movements, reading Bell Hooks, or listening to rastafarian punk band Bad Brains, I would have been much more motivated and engaged with the material. African-American history created by black students makes this course special because we had control over what we would teach, what each lesson would focus on, and the lens through which it would be taught.”

Guerra notes that the energy in the room as Nicholson and Warner taught a sample class to ninth-graders was palpable.

“They provided a range of sources so students could connect the Black Student Movement to their school experience and explore how women created their own spaces in the Black Power Movement,” says Guerra. “Perhaps even more important, the students saw Sanaa and Gabby using history to explore their own stories. Giving students the skills and practice to use history to answer their own questions seems to me to be our central goal. I would not have said that 25 years ago. The continuity is that it is a goal fully consonant with our Quaker belief in the importance of each person.”

Drew Benfer, who has been teaching at AFS since 2005, knoss that human history is also filled with gender and sexuality diversity. Some schools might leave those stories untold and unexplored. Thankfully, that’s not the case at Abington Friends School.

Benfer explains, in the discipline of history, we ask, “What do we know about the individuals from the past? Did they self-identify themselves? If not, is it appropriate for us to identify them now? What sources do we use to study the individuals? What arguments do historians make about the past? What are the consequences of viewing history from a heteronormative lens or by viewing gender as a binary?”

Benfer explores these questions and many more in the semester elective “Gender and Sexuality Diversity in the 20th Century.” To prepare for the course, Benfer spoke with historians at the college level, attended conferences and participated in webinars.

“I want AFS students who identify as LGBTQ+ to know their ancestors and to see themselves in the curriculum,” says Benfer, who every year creates new amazing class content that, quite frankly, most schools wouldn’t allow even though such classes are desperately needed. For instance, he created a semester elective on Constitutional issues, especially the fight for marriage equality.

After teaching “Gender and Sexuality Diversity in the 20th Century” three times over six years, AFS supported Benfer in creating a new semester elective, “Global Perspectives of Gender and Sexuality Diversity.” Benfer and his students are working with an established journalist and author to create a companion guide to a current book on gender and sexuality diversity in the world.

“I feel fortunate to have the full support of my school as we continue to expand the offerings in the History Department,” says Benfer. “I’ll continue to connect AFS students with historians, organizations, scholars, journalists and more who are studying, documenting, archiving, and sharing the stories of LGBTQ+ individuals in the world.”

Community, Connection and Compassionate Learning

Cultivate Resilience, Independence and Resourcefulness

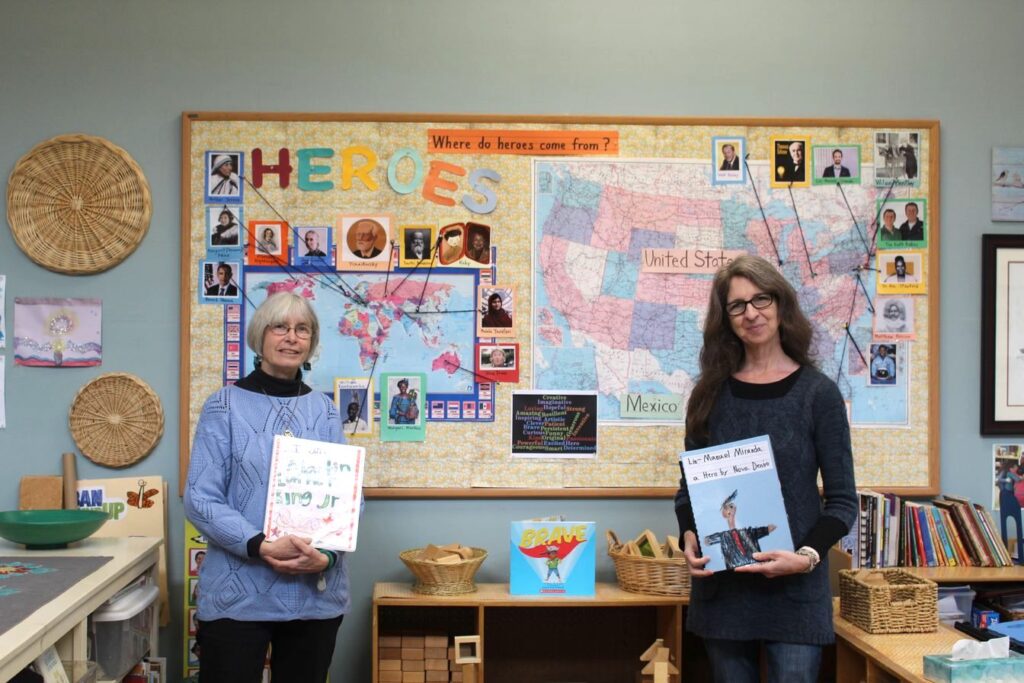

A big piece of early childhood education is getting to know oneself and one’s place in the world. Seasoned AFS first-grade teachers Susan Arteaga and Kathy Lopez know this well.

“In first grade, we meet our students where they are and with what they bring to the class,” says Lopez, who has been teaching for 36 years and retires this year. She was four years old when she announced that she was going to grow up and become a kindergarten teacher. Arteaga, too, had big plans to teach little people ever since she was a child herself.

“I have always been driven to teach young children for as long as I can remember. ,” says Arteaga, who has been teaching for more than 30 years. “I used to play school with stuffed animals and neighborhood kids. Witnessing and nurturing their natural curiosity and awe of learning has always been a beautiful thing!”

Arteaga and Lopez spend a lot of time getting to know their students.

“We find out who the kids are as learners, help them find their voices, and establish some self-confidence to help them navigate through the curriculum pieces,” says Lopez.

For children to be able to learn academics, however, they first have to feel like they belong in the classroom and in the school.

“They have to feel safe, they have to feel known, and they have to feel loved,” says Arteaga.

This is why in first grade, teachers talk about community and the fact that they are all on the same team.

“As a team, they’re putting their energy towards the same goal, learning and growing together,” Arteaga says. Family members are a part of that team, which is why they are invited to visit classrooms and join on field trips and special events. As for belonging, students at AFS not only feel like they are a part of their classroom but also the entire AFS community, and that’s key.

“I love when we’re going to gym class and my students are high-fiving kids in middle school and greeting students in upper school,” says Lopez. “When you’re noticed and appreciated, there’s that sense that you’re a part of this bigger picture.”

Experiential learning is another crucial element to primary education given that students learn in such different ways. Some are auditory learners, others are visual learners. Learning by doing, however, makes the learning process personal and authentic.

“It also makes it very real to them,” says Lopez. “They internalize [the subject] when they are hands-on in the nitty-gritty of their learning. And [what they learn] stays with them longer.”

Arteaga recalls a lesson she taught in which the class worked in teams to take measurements in order to create levers and seesaws.

“They were not learning in isolation. They were learning in community. They were learning in partnership. They were learning by trial-and-error,” she says. “That’s real life.”

One student decided to experiment with trajectory creating a catapult, to see if he could hit the ceiling. Another student piped in that they could only get to a certain height. That’s when they noticed the varied heights of the ceiling so they reorganized the position of their catapults.

“I just feel like they got more out of that than [if they had done]a bunch of worksheets,” says Arteaga. “This is real-world, real-life experiences that make it so authentic and meaningful”.

As students were calculating, measuring and predicting, Arteaga was giddy remembering their joy.

“It was so inspiring to hear their level of excitement and the way that they would start to question each other,” says Arteaga, who videotaped some of the interactions to share with parents so they could witness the joy of experiential learning.

As for measuring student success in first grade, Lopez and Arteaga think well beyond simply the tangible aspect of academics. Instead, they consider emotional success to be the most important realm.

“Seeing them grow as a learner [by] be[ing] able and willing to take risks [is huge,]” says Lopez, because for a lot of kids, that’s really hard to do. “Over the years, I’ve had some very quiet kids and [it can be challenging to] find the way in to help make that connection where they can actually find their voice.” This is why success is not measured solely by academics.

“To me, the social [aspect] is the biggest measure of success—when I feel like I see that child coming into who they are,” says Lopez.

Arteaga loves it when her first-graders begin to reflect back and recognize something they can do now that they couldn’t before.

“That self-reflection is really empowering,” says Arteaga. “There’s joy and confidence that comes from that growth and the pride of those accomplishments.”

Social-emotional learning is an integral part of the first-grade classroom because growth focuses around building resilience, independence, and resourcefulness.

“First-graders tend to find worth by comparing themselves with how they fit in, but it’s important for them to understand and learn that they’re all coming with different gifts, talents, strengths, needs, and goals,” says Arteaga, noting that they also have to be okay with failing. “It’s all about developing stamina, resiliency and inner strength.”

It’s hard when you’re six or seven years old because there’s a lot you don’t know and haven’t yet experienced. At the same time, first-graders know way more than they give themselves credit for, which is why Lopez and Arteaga make sure to document students’ thoughts and words to both acknowledge and honor what they bring to the table. For instance, they do a “heroes on the wall” project in which students are asked to share someone they admire and why.

“Some of their heroes are people I’ve never heard of before,” says Lopez. “They inspire me to want to learn more!”

And let’s be real. As adults, we are always learning from children as sometimes it’s the youngest generation who makes the most poignant, awe-inspiring connections. Case in point: one day Arteaga’s class read a story about a child who was being teased, and a student connected the dots and said, “Bullying is just like COVID. You have to stop it before it spreads.”

Arteaga thought, “Oh, my gosh! What a brilliant connection!” And then the class engaged in a conversation about how to handle teasing situations with care and compassion.”

This is why being a lifelong learner is such a great thing. It means that you’re never finished learning…and therein lies the beauty.

This is why being a lifelong learner is such a great thing. It means that you’re never finished learning…and therein lies the beauty.